ALIAĞA—The anger is palpable in Aliağa, a heavy industrial hub on Turkey’s Aegean coast. Although the town has long been infamous for its high rate of workplace deaths, the killing of shipbreaker Hasan Aktepe on Nov. 12 struck a particular nerve.

In the late afternoon of that day, while dismantling the base of a large oil rig, Aktepe climbed under a massive metal slab to drill a hole and drain the water from inside. Apparently, he was unaware that a colleague was cutting above him.

An estimated 80 tons of scrap broke loose and crushed Aktepe. He had just turned 45 the day before and was planning to buy a car the weekend after.

“I don’t understand this last death,” said a former shipbreaker in Aliağa. “It is pure stupidity. If someone is cutting on the top, why would anyone be sent down to the bottom?”

“It was because they were made to hurry,” added another worker who was on that very yard when Aktepe was killed. “The workers were told to finish the job that day.”

“This was entirely preventable,” Prof. Alp Ergör, a public health professor at Izmir’s Dokuz Eylül University and former labor inspector, told Turkey recap.

Yet he is not surprised. A dangerous combination of prioritizing speed over safety, a lack of oversight and impunity for negligence has driven many workers in Turkey to their graves. The country has long been ranked among the worst and most hazardous places to work. This year appears to be no exception.

At least 1,736 workers died on the job in the first 10 months of 2025, Turkey’s Health and Safety Labor Watch (ISIG) reported. This November alone saw a string of high-profile workplace fatalities, including seven female workers — three of them underage — killed in a cosmetics factory fire, and a fifteen-year-old carpenter reportedly tortured to death.

By comparison, across the entire European Union, 3,347 fatal occupational accidents were recorded in 2023, according to the latest Eurostat figures.

Despite clear negligence in the case of Hasan Aktepe, no one Turkey recap spoke with expects anyone to be held accountable or any substantial changes to follow. The family will receive some compensation, and no charges will be pressed—a practice considered commonplace.

A few days after Aktepe was laid to rest, work resumed at the yards. Just as it did six weeks earlier, when another shipbreaker, Halil Ibrahim Uz, fell to his death.

Leading causes of death

ISIG estimates that since the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002, a minimum of 35,000 workers have died. This averages about five deaths per day in Turkey, with at least one child worker and two elderly workers killed every week.

“Since ISIG started in 2011, it has been either the construction or the agricultural sector that causes most deaths,” ISIG member Aslı Odman told Turkey recap. However, industries like shipbreaking, mining and motorcycle delivery services have relatively the highest mortality rates.

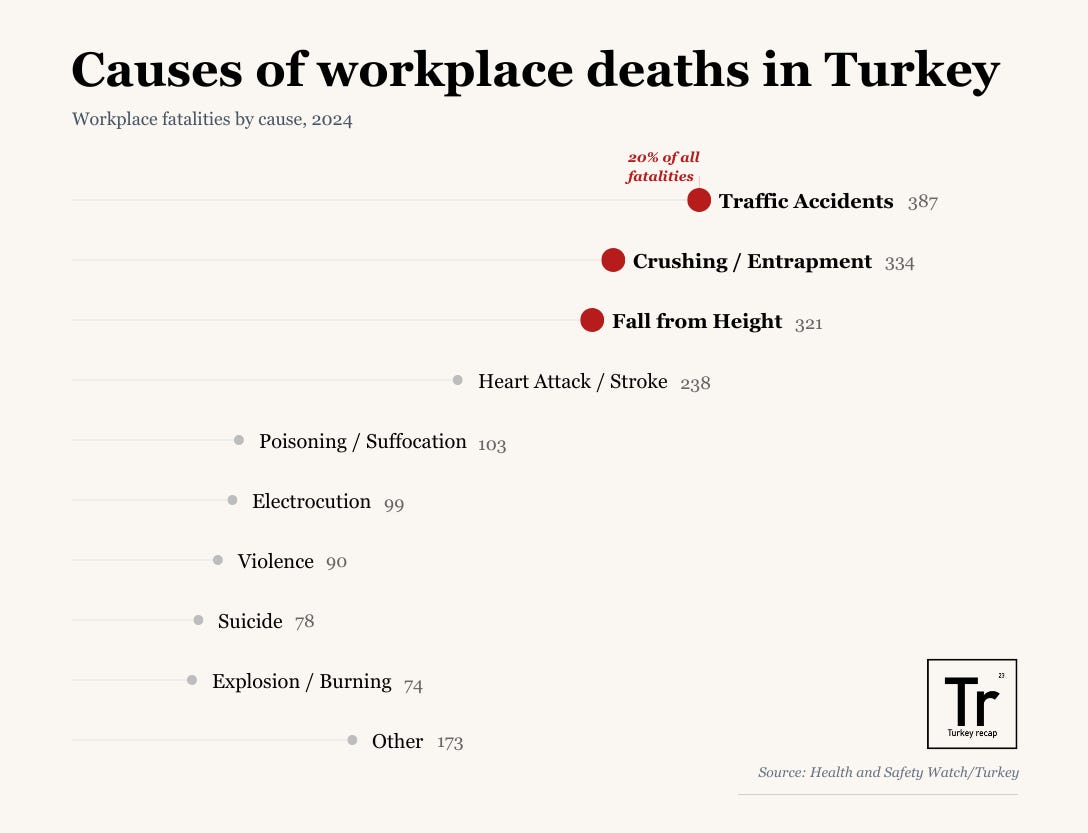

Last year, traffic accidents, falling from heights and getting crushed were the leading causes of death among the nearly 1,900 workplace fatalities recorded by the labor watchdog.

These figures are likely an underestimate, Odman noted, as the organization largely relies on news and social media reports, which mainly capture “sudden deaths”.

Fatalities due to occupational diseases often do not make it into the count—although their death toll is an estimated two to seven times that of workplace accidents, according to Odman.

Yet, she believes these numbers are still more comprehensive than the official occupational data from Turkey’s Social Security Institution (SGK), as their data often does not include unregistered workers or ongoing court cases.

Turkey’s Ministry of Labor and Social Security did not reply to Turkey recap’s request for comment.

Lack of inspection and accountability

One of the main reasons behind worker deaths, according to Sevda Karaca, an MP for Turkey’s Labor Party, stems from employers cutting corners by deliberately ignoring safety measures to boost profits.

“Occupational safety and worker health in workplaces are treated as costs, and workers’ lives are sacrificed in cost-benefit calculations,” Karaca told Turkey recap. She added that safety rules are often viewed as measures that slow the pace of work and, therefore, only exist on paper.

Karaca and ISIG insist on using the term “workplace homicides” instead of “occupational deaths” to emphasize that these fatalities are preventable.

Workplace safety specialists have increasingly less independence due to privatization since legal changes in 2013. According to Ergör, they cannot enforce regulations effectively and face immediate pressure when they push for costly or time-consuming safety measures. Workers in shipbreaking yards in Aliağa also confirmed this.

“Occupational safety specialists and workplace doctors are [now] the employer’s employees,” Ergör said.

Moreover, when accidents occur, those higher up often face no punishment or only minor penalties, both Ergör and Karaca said. Most recently, following a deadly explosion in 2024 at a pasta factory in Sakarya, the owners escaped trial while the occupational safety expert and other administrative personnel received hefty prison sentences.

State oversight and inspections, when they occur, are also often described as ineffective. The Sakarya factory was subject to inspections by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security one month prior to the blast.

This is a rare occurrence, as reportedly only four out of every 10,000 businesses are examined by ministry inspectors annually, with fewer than 1,000 labor inspectors overseeing over 2 million businesses.

“[Even during] government inspections, they [the bosses] know exactly which day and hour they are coming,” another shipbreaking yard worker told Turkey recap. “That day, everything is cleaned up. I know because I did it. Those days, serious protective gear is handed out.”

A new deadly trend

In Turkey’s fast-growing gig economy, motorcycle delivery drivers risk death on the roads daily. They mostly deliver takeout food and parcels bought on Amazon-style web stores, and are legally considered self-employed. On average, one delivery driver gets killed each week.

“They tell us ‘you’re a boss, not a worker,’” Mesut Çeki, head of the Delivery Worker Rights Association, told Turkey recap. “But this is a lie! Many people want to work without a boss. They use this sentiment to trick people.”

For example, the delivery drivers working for the widely used Yemeksepeti food delivery app can decide for themselves how much they work and when. The gross income also looks enticing on paper. But most of the advantages end there.

As self-employed, they have no paid leave, health or other kinds of insurance, severance pay, right to join or form a union, or any of the other traditional workers’ rights.

“To make ends meet, a motorcycle courier has to deliver at least 50 to 60 packages a day,” Çeki added. “That leads to working 70 to 80 hours a week. How good can one’s reflexes be after having worked for 12 hours [in one day]? How can they adhere to traffic rules with such a workload?”

Çeki himself started working as a motorcycle delivery driver during the Covid pandemic after he lost his job.

One day, he was told that he needed to “urgently” deliver some sushi to a luxurious part of Istanbul in the middle of a storm. This angered him so much that he started an online platform that eventually evolved into the Delivery Worker Rights Association.

“The deaths of delivery drivers are not because of individual mistakes. Couriers are dying, being killed, as a result of the system,” Çeki asserted.

One of the high-profile delivery driver deaths was that of Samet Özgül. He was working for Trendyol GO in Ankara when, in 2022, he got into an accident. It quickly turned into a brawl, and Samet was fatally stabbed.

“I have been seeking justice for my brother Samet since 2022,” Berna Özgül told Turkey recap. Only one of the three attackers was sentenced. In her pursuit of justice, Özgül also became a council member for the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP).

“There is a widespread perception in Turkey right now concerning motorcycle delivery drivers—that they make a great deal of money, are their own bosses and have an easy time of it. In reality, that is not the case.”

Back in Aliağa, the work continues in the shipbreaking yards. Those who are crushed or fall to their death on the job are sometimes not even the unluckiest ones. Because of the hazardous materials they handle, many develop cancer and other fatal illnesses, leading to long and excruciating deaths.

“I have to continue for now,” said the shipbreaking worker whose colleague recently died. “If I find another job for the same wage, I will leave that very day, of course. I know that [here] I will die prematurely.”

Turkey recap is an independent, reader-supported newsletter that helps people make sense of the fast-paced Turkey news cycle. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Subscribe here on Substack (or on Patreon for discount options). Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools.

We are an affiliate of the Global Forum for Media Development and aim to create balanced news that strengthens local media by supporting journalists in Turkey.

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief

Emily Rice Johnson, Deputy editor

Ceren Bayar, Parliament correspondent

Yıldız Yazıcıoğlu, Parliament correspondent

Günsu Durak, Stüdyo recap editor

Demet Şöhret, Social media and content manager

It is this kind of reporting -- clear, comprehensive and immediate -- that helps this reader work to stay in touch from 7500 kms away from Istanbul. Tebrikler ve teşekkürler