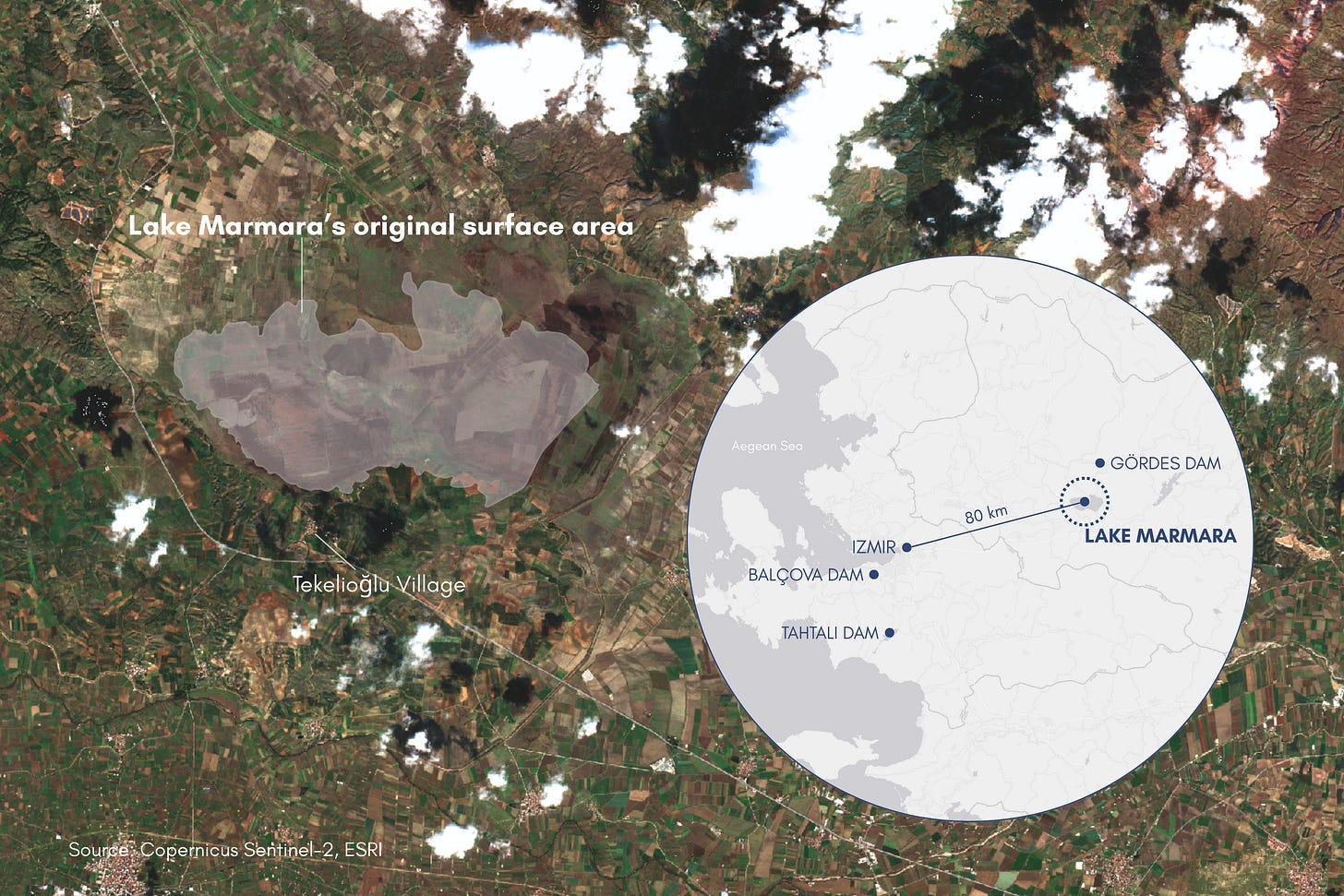

MANISA—On a foggy mid-December morning in Tekelioğlu, a village in Turkey’s western Manisa province, Ferit Erefe strolls along the edges of Lake Marmara. But as the unseasonably strong sunlight cuts through the mist, it reveals a flat, arid plain instead of water. Decaying fishing boats dot the dried shoreline.

A protected wetland once spanned about 45 square kilometers here. Its abundant carp stocks sustained dozens of households, including those of Erefe and his father, as well as thousands of waterbirds that flocked to the reservoir to breed and pass the winter. Today, cattle graze the green-brown land as an upstream dam has cut off the water flow.

“How are we going to explain this to our children?” Erefe mutters, standing next to one of the boats. “That there was a lake here. That we used to fish here.”

Lake Marmara is one of many freshwater bodies that have vanished across Turkey in recent decades. Since the 1960s, an estimated 186 of the nation’s 240 lakes have been dried up, along with nearly 1.5 million hectares of wetland.

The trend is wiping out livelihoods and ecosystems, and is set to escalate as Turkey approaches a ‘water-poor‘ status, with some regions facing severe desertification by 2030.

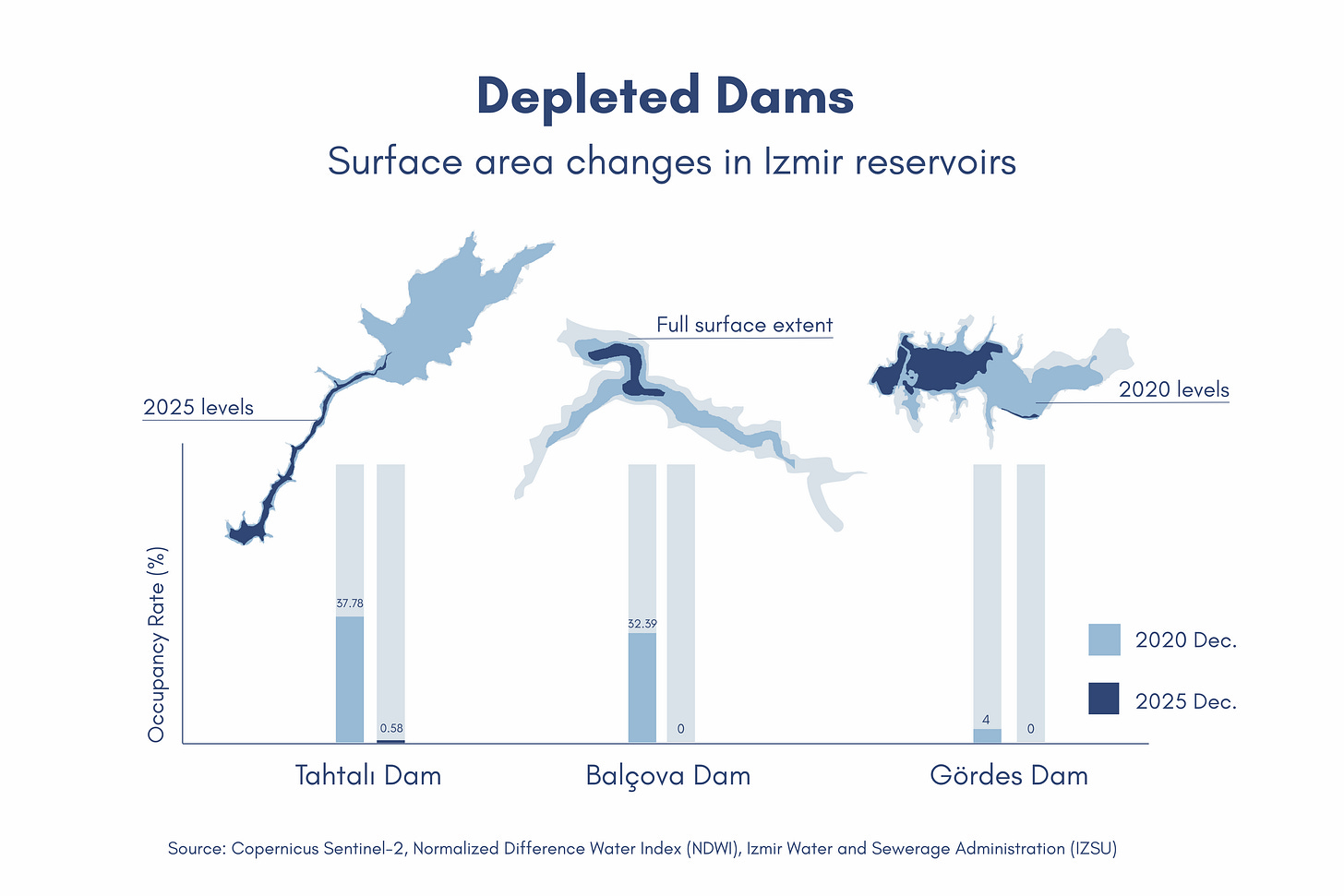

The past year marked Turkey’s driest period in over half a century, with above-average temperatures and rainfall shortages disrupting food production and driving up prices, while leaving nearly all major cities with alarmingly low water supplies.

Yet, the steady decline of Turkey’s freshwater resources is driven not merely by climate change and drought, but also by weak safeguards and mismanagement.

State policies have permitted profit-driven ventures, such as dams and mines, to seize natural assets vital to the water cycle, reducing Turkey’s capacity to cope with looming water risks, said Selma Akdoğan of Izmir’s Chamber of Environmental Engineers.

“If necessary measures are not taken, the situation will worsen,” Akdoğan warned.

In this light, Lake Marmara’s evaporation in 2021 was less about climate change, and more tied to the 2009 completion of the Gördes Dam—a project intended to quench the thirst of nearby Izmir and surrounding farmlands that has been hampered by faulty construction, preventing it from retaining sufficient water.

“Climate change is a contributing factor in the water crisis, while inadequate water management is the determining factor,” Dursun Yıldız, head of the Hydropolitics Association, told Turkey recap.

Urban and agricultural demand

Most of the reservoirs serving Izmir and its surroundings, including the Gördes dam, are currently bone-dry. Their ‘dead storage’ is being drained to supply nearly 5 million residents and farmers in the fertile Gediz basin, where locals have struggled with daily water cuts and other conservation measures for months.

Simultaneously, much of the remaining supply currently comes from local groundwater—a renewable but finite resource that requires stringent oversight to prevent over-extraction and other adverse effects like salinization and the formation of sinkholes, as observed in Turkey’s Konya province.

“Our water resources are under pressure both in terms of quantity and quality,” Akdoğan said.

These shortages haunt Turkey’s agricultural sector, the world’s 7th largest, accounting for about 6 percent of GDP and consuming over 75 percent of the country’s water reserves. A recent UN report predicts up to four-fifths of the nation’s farmland could face severe drought within a decade.

“It’s like a desert everywhere,” Mehmet Ali Kerse, a former Tekelioğlu fisherman who turned to cultivating olives, told Turkey recap.

Along with Lake Marmara—which locals said helped produce larger, higher-quality olives by providing irrigation and a cooling summer microclimate—most of the village’s wells have also dried up.

In Gölmarmara, a town between Lake Marmara and the depleted Gördes Dam, grape farmer Muzaffer Günaltay grapples with similar problems, stating water wells need to be drilled deeper and new ones are banned by local authorities.

“My [farmer] neighbor has run out of water,” Günaltay told Turkey recap. “They were going to drill for water. There was no permission. They did it illegally and got fined.”

He said his well suffices for now, but renewed dry spells can easily cut grape harvests by a fifth.

“I believe [drought] represents a grave danger. It is one of agriculture’s biggest problems,” he added.

To combat the growing scarcity, Akdoğan said it is paramount to pursue alternatives like water harvesting and recycling while simultaneously curbing demand from water-intensive industries.

Despite its vast scale, much of Turkey’s agriculture still relies on inefficient irrigation methods such as flood and furrow systems instead of sprinkler and drip irrigation, which can cut water use by half.

Eternal dam nation

Further worsening Turkey’s water crisis is that many of its dams were designed to fail.

Over the past decades, companies with close ties to the government have secured large contracts for hydraulic works that flood villages, dry up nations downstream of Turkey and devastate the environment, all while failing to deliver on their much-anticipated promises.

The Gördes Dam, marred by cracks and leaks, has not maintained significant water levels since its opening. Geological studies had long warned that the ground—made of permeable limestone—was unsuitable for a reservoir. The dam was built regardless, funneling 170 million dollars into the pockets of its contractor.

“No matter what they do, it [the Gördes Dam] will always continue to crack,” Özgür Bal, a local geological engineer, told Turkey recap. “It is a meaningless project, and they’ve killed a natural lake with it.”

In the absence of Lake Marmara, once-thriving fisheries perished, thousands of migratory birds recharted their ancient routes and many tortoises were found suffocating in troughs and wells.

The economic backbone of nearby communities also snapped, forcing many residents to migrate in search of work.

“For younger generations, incomes have become too low,” Erefe said. “[They] can’t even get married anymore.”

Bal went on, stating the dam’s reservoir cannot replace the diverse habitat that Lake Marmara once provided. The stocked fish lack flavor, and instead of swamps where waterbirds can feed and breed, the dam’s environs consist of concrete and rocks, forcing birds to use it only as a temporary transit point.

“After resting for half a day, they get up and head out,” Bal said.

Legal efforts to restore Lake Marmara

Despite such changes, some groups continue to push back on government interventions in the region.

Civil society organizations successfully filed a lawsuit in 2024, halting the lake’s conversion into agricultural land by a state-run agency. In its ruling, the court emphasized the importance of wetlands in the face of global climate change.

“They say that the lake can be saved,” Yıldıray Çıvgın, an environmental lawyer handling several legal cases related to Lake Marmara, told Turkey recap.

A solution proposed by the local governorate would leave the Gördes Dam intact while diverting water to Lake Marmara from elsewhere, a plan met with skepticism, according to Çıvgın.

“A lake cannot be made with carried water,” he said, playing on a Turkish proverb that a mill cannot turn by carrying water.

Yet, new projects continue to threaten water resources. The lawyer is now challenging governor-approved sand mines that have begun impacting the tributaries once vital to the lake’s survival.

“Is it like trying to treat a patient who already passed away?” Çıvgın asks. “I don’t want to believe that. We’re really doing quite a lot. As much as we can.”

Turkey recap is an independent, reader-supported newsletter that helps people make sense of the fast-paced Turkey news cycle. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Subscribe here on Substack (or on Patreon for discount options). Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools.

We are an affiliate of the Global Forum for Media Development and aim to produce balanced news that strengthens local media by supporting journalists in Turkey.

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief

Emily Rice Johnson, Deputy editor

Ceren Bayar, Parliament correspondent

Yıldız Yazıcıoğlu, Parliament correspondent

Günsu Durak, Stüdyo recap editor

Demet Şöhret, Social media and content manager

This is incredibly scary, given the various water crises in Turkey and around the world, and even scarier when you realize that none of the current state systems -- bent, as they are, almost religiously on maximizing profit, denigrating science and expertise, and reducing regulations of any kind -- will do anything to stop it.