ISTANBUL — On a Saturday morning, in Istanbul’s usually quiet northwest, the two-lane road between Lake Terkos and the Sazlıdere Dam is bustling.

Countless trucks thunder past signs from the city’s water utility, ISKI, that warn: ‘This is a drinking water basin. No construction allowed.’ They are hauling loads to thousands of government-backed housing units that are springing up nearby.

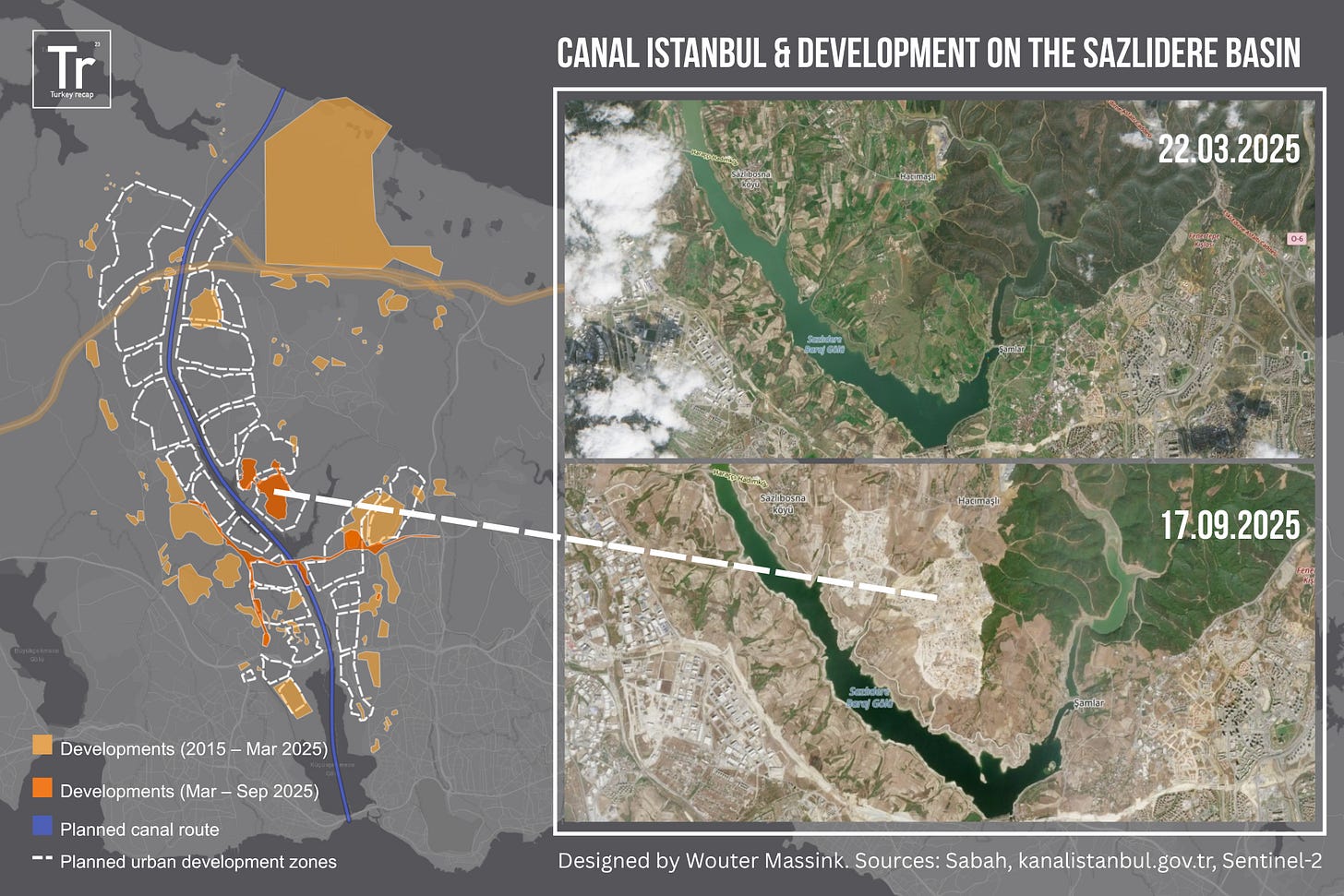

A building frenzy has gripped Istanbul’s northern green belt — home to some of the city’s most vital water reserves — following the March 2025 imprisonment of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoğlu on alleged corruption charges. This has fueled speculation that the controversial Canal Istanbul project is back on the table and that Imamoğlu’s jailing is tied to it.

Announced in 2011 by then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as his “crazy project,” the canal would carve a 45-kilometer waterway parallel to the Bosphorus, flanked by residential and commercial real estate.

Intended to ease traffic on the busy strait and provide earthquake-resistant housing, the shipping channel would cut through freshwater reserves, forests, marshes and farmland to link the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara.

Canal Istanbul was meant to be the crown jewel of a series of megastructures Erdoğan has planted over the past decade in Istanbul, including Europe’s largest airport, highways, tunnels and a third bridge over the Bosphorus.

However, financial woes, general unpopularity and staunch public opposition — including by Imamoğlu — along with court rulings against zoning plans, have so far prevented the canal from being built. The mayor has consistently denounced the waterway as a betrayal of Istanbulites, emphasizing its projected environmental impact and risk to the city’s freshwater supply.

“The people will stop your concrete canal, your love for luxury housing, your profiteering projects and your new betrayals of Istanbul,” Imamoğlu wrote in a social media post from prison after the first bulldozers were spotted near the Sazlıdere basin in early April.

But with much of the opposition under a judicial pressure campaign, experts told Turkey recap that little now stands in the way of a construction surge — with or without the canal — that could wipe out Istanbul’s last pockets of biodiversity and further endanger already strained water supplies.

Building on nature reserves

“Whether water will actually flow or not is not that important,” Emre Kovankaya, an urban researcher at the municipality-affiliated Istanbul Planning Agency (IPA), told Turkey recap.

Kovankaya said the canal plans have functioned as a spearhead to open the area for speculative real estate ventures. These projects, which have been bundled under the name “Yenişehir” or “New City”, are along the canal’s intended course.

The area sits atop protected forests, farmland and water basins that have gradually been opened to construction through a series of legal maneuvers, including the controversial 6306 law.

Currently, the state housing agency TOKI, its corporate arm Emlak Konut and an array of government-linked firms reportedly began building over 40,000 housing units in the region — part of the largest social housing scheme in Turkey’s history.

These residences are not luxury homes and not part of Canal Istanbul, Urban Planning Min. Murat Kurum stressed in April.

Yet Kovankaya and Pelin Pınar Giritlioğlu, an urban planner at Istanbul University and former head of the city’s Chamber of Planners, believe the new homes are being built for prospecting investors.

Since the canal’s announcement, reports have surfaced of prominent figures — like former Finance Min. Berat Albayrak and Sheikha Moza, the mother of Qatar’s emir — acquiring plots along the route. Moza’s farmland was recently opened for commercial purposes by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization.

“Social housing is being used as an excuse,” Giritlioğlu told Turkey recap. She added that when the Chamber requested information from the Ministry on the social and economic status of homebuyers, they received no response.

Previously, an Istanbul court blocked the Yenişehir development plans in 2024 over environmental concerns. However, a new zoning plan was pushed through in early 2025.

The shift came despite public opposition. A recent IPA survey found 77 percent of respondents opposed the canal, citing suspected profit motives and environmental concerns.

Yet, according to a 2025 semiannual report from Emlak Konut, the Yenişehir Evleri — built in stages along the canal’s route — ranked highest on its sales list with 5,705 residences sold in the past 18 months, generating over 36 billion Turkish lira.

Meanwhile, Transport and Infrastructure Min. Abdulkadir Uraloğlu recently stated the government has not abandoned the canal and is waiting for the right financing.

“Everyone knows this project is a massive ecological disaster,” Giritlioğlu said. “Yet it is being pushed forward because there is a huge real estate profit at stake.”

Sazlıdere reservoir

One of the focal points of the current canal controversy has become the Sazlıdere Dam. The 29-year-old reservoir on Istanbul’s European side normally supplies water to about 750,000 people.

After Imamoglu’s arrest, countless TOKI-built high-rises have been shooting up just a few hundred meters from the waterfront, adjacent to a large bridge that is taking shape, where Pres. Erdoğan laid the canal’s foundation in 2021.

These constructions, part of a 2.5 million-square-meter real estate project, come on the heels of reports that the dam was stripped of its official status as a drinking water source by presidential decree in September 2022. ISKI, which oversees the dam, said it was only recently informed.

ISKI deemed the constructions in violation of the Water Basin Protection Regulation and issued a demolition order in April. Several senior ISKI officials were later detained in a broader crackdown on the opposition-run municipality. In May, a court annulled the demolition order after TOKI objected.

“In the last two decades, the growth of the Turkish economy was based on construction,” Berkan Özyer, director of Greenpeace Turkey, which has campaigned against the canal for years, told Turkey recap. “But there were some relatively working checks and balances against construction projects.”

Özyer said that resistance through the legal system or other forms of opposition seems to have become increasingly ineffective. Moreover, with municipal figures removed, little now blocks the ramping up of construction, Giritlioğlu warned, which could have devastating consequences for the city’s water supply.

According to Minister Kurum, however, Sazlıdere’s housing complies with regulations and zoning plans and will neither harm water resources nor the dam itself. Turkey’s Center for Combating Disinformation also strongly denied claims that the 2022 decision could trigger a “water crisis” in Istanbul.

Yet, even minor changes in Sazlıdere Dam’s capacity could have major consequences, Dursun Yıldız, former head of the drinking water department at Turkey’s State Hydraulic Works (DSI), told Turkey recap.

Like much of Turkey, Istanbul is under growing water stress, with scarcity differing between its two sides. About 65 percent of the population lives on the European side, while most reserves are on the Asian side, Yıldız explains.

“Sixty percent of the water demand on the European side is supplied from the Asian side,” Yıldız told Turkey recap, noting the 61 percent drop in Sazlıdere’s capacity, as projected under the Canal Istanbul plan, could increase the European side’s dependency on retrieving water from faraway sources.

”The Sazlıdere Dam is regionally important for water security," Yıldız said, adding that “the European side experiences longer drought periods, has a larger population and its stored water volume is insufficient.”

Hopes, therefore, rest on the Melen Dam, whose construction began in the mid-2000s and is scheduled to secure Istanbul’s water needs until 2071 by delivering water from the Melen River, 170 km west of the metropolis. The project, however, has been plagued by delays, faults and cracks.

Paved over

Aside from looming water challenges, a recent court-ordered report on Canal Istanbul found over 4,674 hectares of agricultural land and 2,491 hectares of forest along the route are at risk.

This could further erode the region’s unique ecology, home to an exceptional plant diversity, Cihan Erdönmez, assistant professor at Istanbul University’s Department of Forestry Engineering, told Turkey recap.

Due to its unique position between the Mediterranean and Black Sea, Istanbul hosts about 2,500 plant species, far more than countries like the Netherlands, which has 1,600 species despite being eight times larger.

However, at the hands of megaprojects, Istanbul’s forests, marshes and farmland have been shrinking rapidly in recent decades, with the third bridge, its linked highway, and the new airport estimated to have cost the city nearly 100 square kilometers of forest and more than 140 square kilometers of farmland.

”The truth is that Istanbul’s nature and greenery are continuously bleeding,” Erdönmez told Turkey recap, adding this inevitably destroys the habitats upon which many species depend.

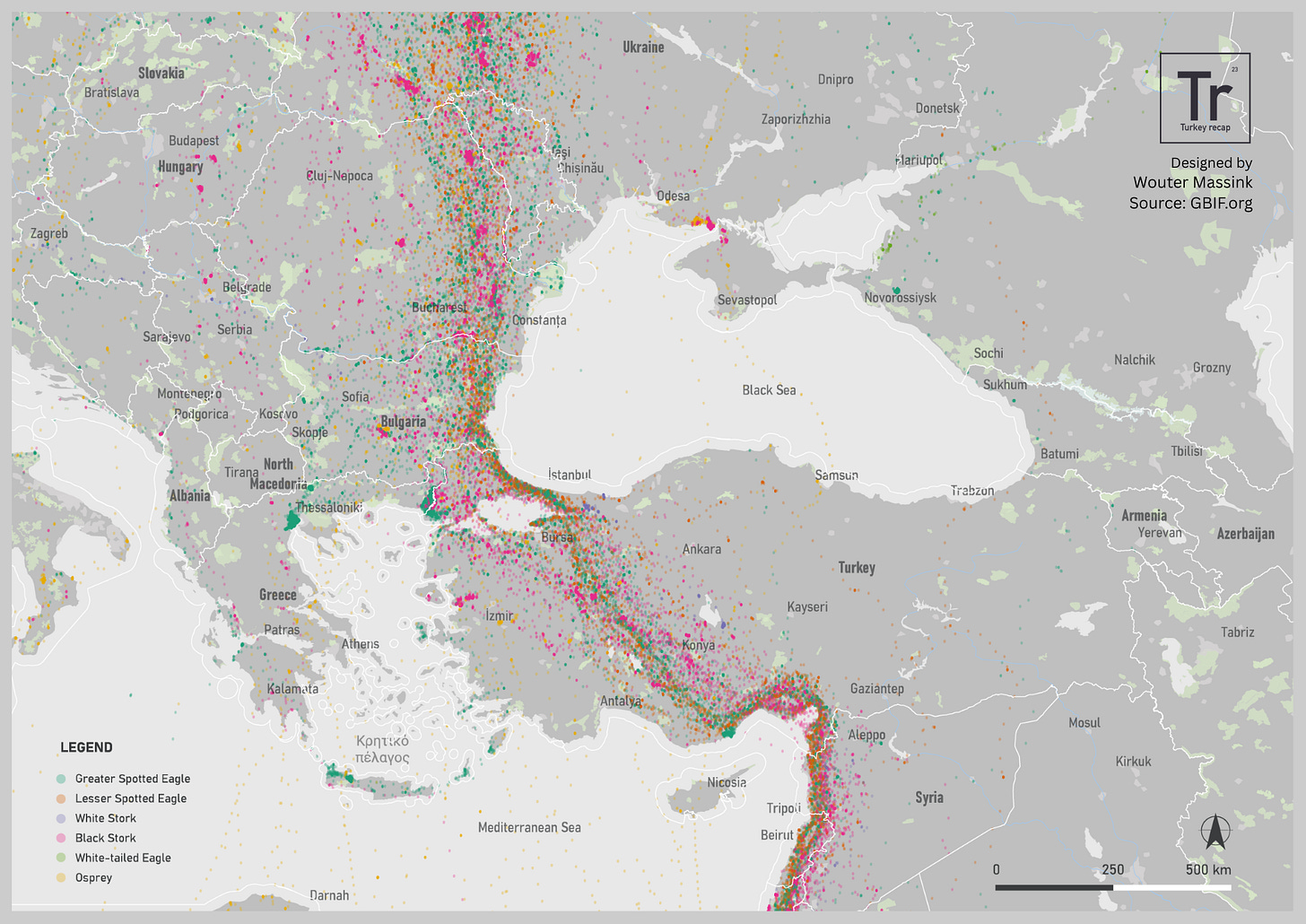

This includes many of the world’s migratory birds — such as hundreds of thousands of storks, raptors, passerines and waterfowls — which use Istanbul as a vital pit stop each spring and autumn on their travels between Eastern Europe and Africa.

During their long flights, soaring migratory birds utilize thermal air currents to conserve energy. These are primarily found over landmasses, turning Istanbul into a bottleneck during their journeys, said Şafak Arslan, a biodiversity research coordinator at Doğa Derneği.

“[It] forces these birds to pass over,” Arslan told Turkey recap.

At the same time, migratory waterbirds consume large amounts of energy when crossing the Black Sea.

“They travel long distances and arrive exhausted,” Arslan said, adding this makes direct landings in Istanbul’s ever-decreasing wetlands necessary.

“These interventions will destroy the remaining refuge areas for the birds,” he added, referring to development projects in Istanbul’s northern green belt.

Turkey recap is an independent, reader-supported newsletter that helps people make sense of the fast-paced Turkey news cycle. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Subscribe here on Substack (or on Patreon for discount options). Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools.

Turkey recap is produced by our staff’s non-profit association, KMD. We are an affiliate of the Global Forum for Media Development and aim to create balanced news that strengthens local media by supporting journalists in Turkey.

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief

Emily Rice Johnson, Deputy editor

Günsu Durak, Turkey recap Türkçe editor

Ceren Bayar, Parliament correspondent