ISTANBUL — Turkey has the world’s seventh-largest agriculture sector. It produces three quarters of the world’s hazelnuts along with millions of tons of cherries, grapes, almonds, walnuts and other fruits.

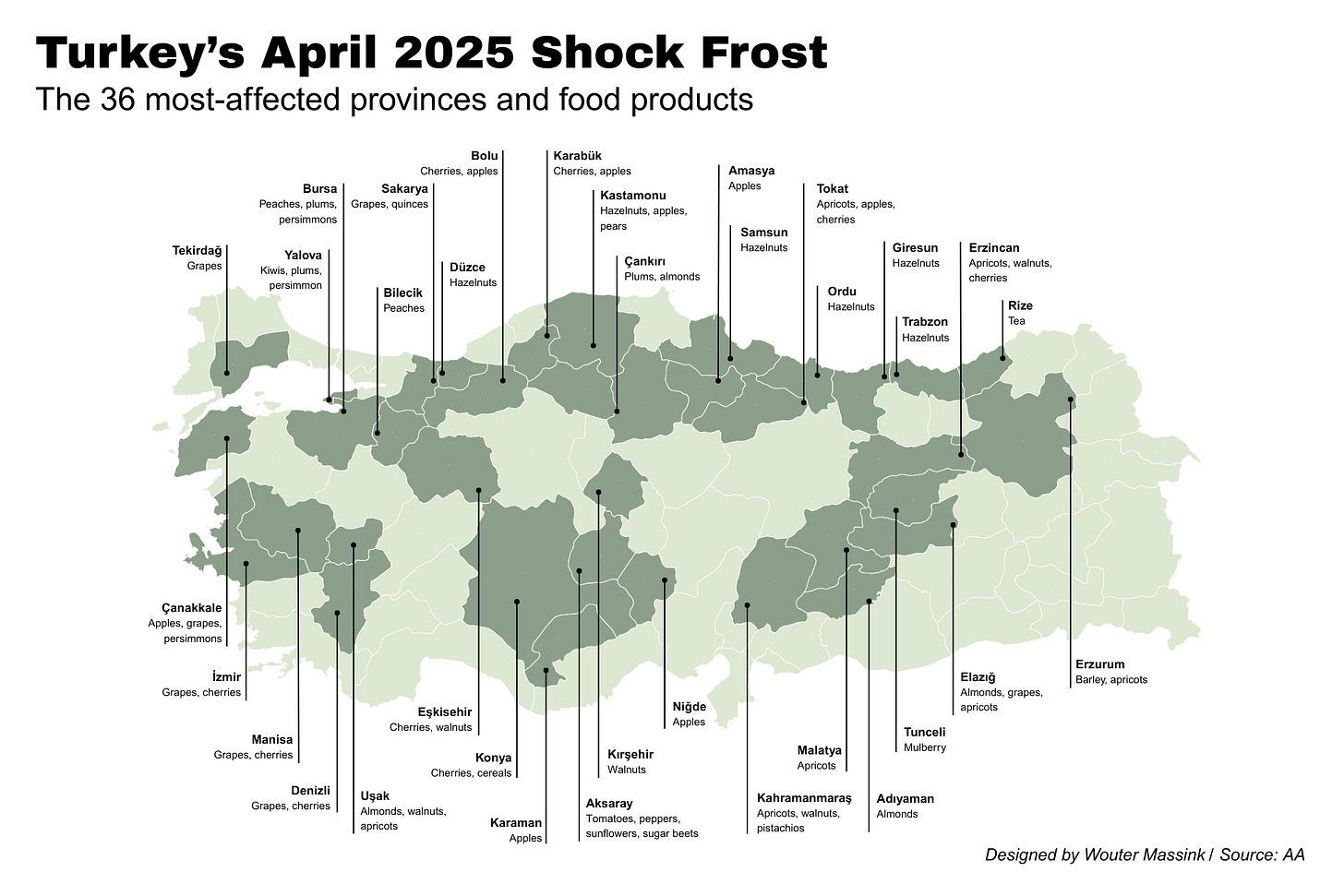

But in April, many of those crops were damaged by a devastating late-spring frost. The freak weather event caused irretrievable losses on farms in almost half the nation’s provinces, deepening pressure on global and domestic food prices, which were already rising at a record rate in Turkey.

The impacts are immediate and long-lasting, as orchards may take years to recover. Among the worst affected sectors was the world’s dried apricot market, nearly two-thirds of which is supplied by Turkey.

The nation’s apricot output is set to collapse from 750,000 tons to 10,000 this year, contributing to a near 50 percent fall in global production and driving up prices by as much as 300 percent in recent months.

“This was like an earthquake in agriculture,” Omer Fethi Gürer, a deputy for the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), told Turkey recap.

Gürer represents the rural province of Niğde, where an estimated 95 percent of all apple production evaporated. He also serves on a parliamentary commission addressing the frost’s aftermath.

Though estimates vary, the commission currently puts state-insured (TARSIM) farmers’ losses at over 21 billion liras with expected annual fruit output plunging 7 million tons. As a result, up to a million agricultural jobs could vanish, hitting Turkey’s second-biggest employment sector and a major source of work for women.

Recovery efforts are ongoing, but complicated by farmers’ limited access to protective measures, insurance and state support amid rising maintenance costs, according to agriculture experts.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s agriculture sector remains highly vulnerable to erratic weather patterns, which occur with increasing frequency due to global climate change.

Unseasonal frost, unusual prices

The most destructive unseasonal frost in over 30 years spread across Anatolia from April 10 to 13, with temperatures dipping to -15°C just as fruit trees bloomed. Farmers scrambled day and night, lighting car tires and paraffin candles or spraying smoke and water to fight the freeze – mostly to no avail.

“I spent my nights there [in the field] until the morning,” said Doğan Aralongun, one of the few grape farmers from Manisa who managed to save most of his crops by using a sprinkler system.

“I constantly checked the thermometer. As soon as it dropped below one degree Celsius, I turned on the sprinkling systems,” Aralongun told Turkey recap, adding that his low-altitude location closer to Manisa’s warmer center also helped him avert the worst impacts.

“This was the first time frost hit in such a widespread manner,” Ali Bülent Erdem, head of the farmers’ union Çiftçi-Sen, told Turkey recap. “It affected almost all crops, but especially perennial plants.”

About half of the financial losses were grapes, while hazelnuts and apples were also severely weather-beaten. The western Anatolian province of Manisa, famous for its Sultaniye grapes, was hit worst: up to 90 percent of its vineyards were ravaged, amounting to 10.97 billion liras in damages.

“This year, instead of 40 tons of dried grapes, I’ll only produce 20 or 25 tons,” Haşim Lımanlar, a grape farmer in Manisa, told Turkey recap.

Compounding the blow, Lımanlar said most costs were incurred before the frost, while the damaged buds will likely trim next season’s yield by another 10-20 percent.

“It’s frustrating … After all, it’s hard work lost,” Lımanlar said. He added that switching to growing his grapes in more weather-resistant greenhouses is currently out of the question due to the high costs.

All these losses will primarily be transferred to consumers, Gamze Saner, a professor at Ege University’s agricultural department, told Turkey recap.

“As a product’s supply decreases, prices at wholesale and retail markets rise,” Saner said. “This increase triggers food inflation.”

Turkey’s food inflation has long been a pressing problem, with annual rates nearly five times higher than the world average.

Citing the cold snap as the key culprit, Turkey’s Central Bank raised its 2025 food inflation forecast to 26.5 percent. This is set to further deepen the country’s growing wealth distribution, Saner warned. Meanwhile, the government stressed that the country’s strategic food supply is not at risk.

Yet prices for certain affected products, such as grapes, have remained relatively stable for now, farmers told Turkey recap. Ömer Ayhanlı, a vineyard owner in Denizli who lost about 20 percent of his wine grapes – worth roughly half a million lira – said already low demand from wineries would keep prices from spiking.

Nutella problems

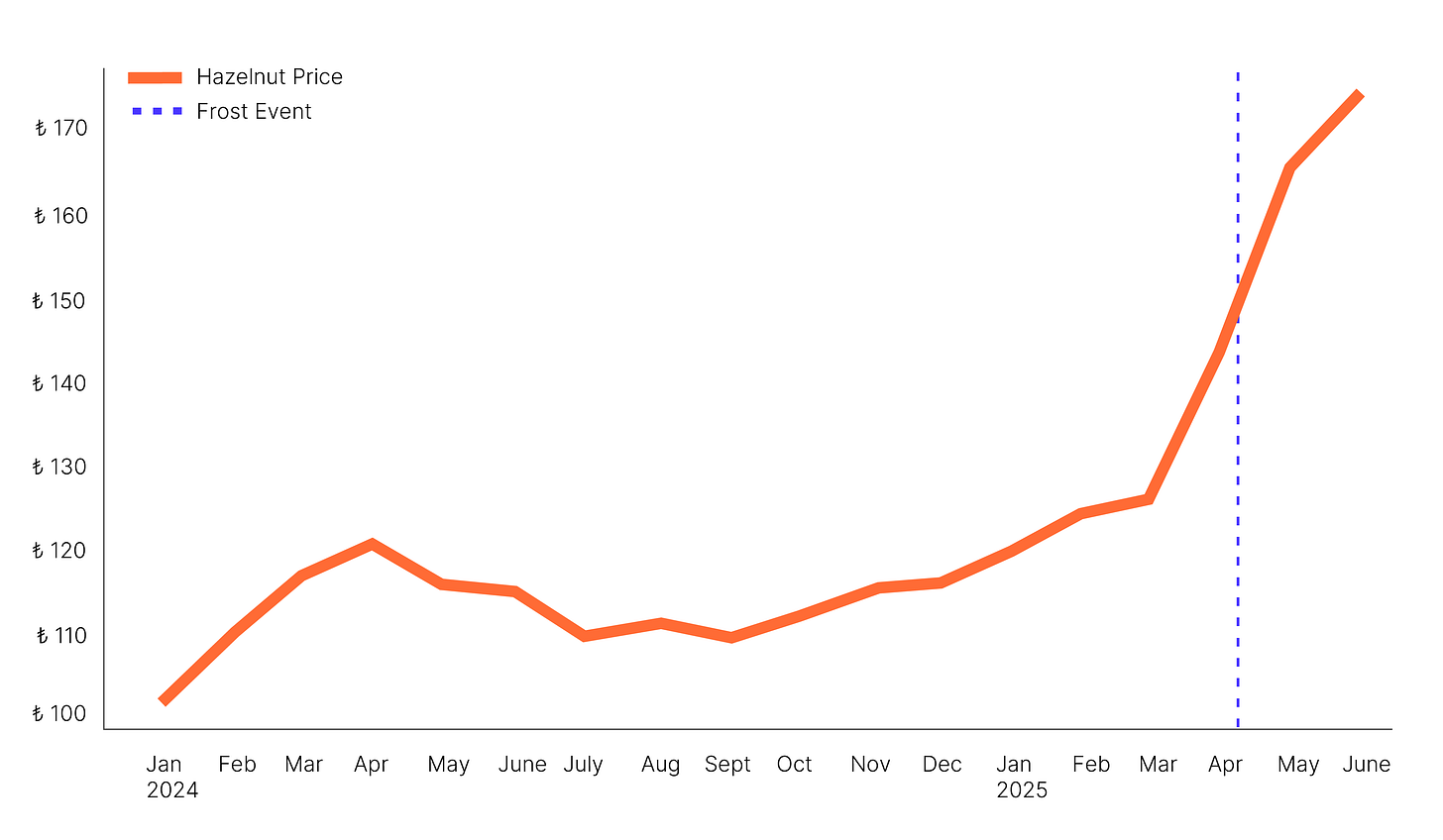

Besides fueling domestic food inflation, the frost’s impacts ripple through international markets. Especially crops where Turkey is a top producer have seen significant price jumps.

Turkey supplies roughly 70 percent of the world’s hazelnuts. Italian Nutella maker Ferrero snaps up a quarter of that. With an expected third of the nuts now lost, Nutella fans must brace for expensive spreads in the coming months.

“Currently, prices have increased by approximately 50 percent,” Özer Akbaşlı, a hazelnut farmer from Giresun, told Turkey recap, whose crops survived thanks to cultivating at a lower altitude.

The nut’s value is expected to climb further. In 2014, a similar frost event killed 30 percent of the country’s hazelnuts, tripling global prices.

Such sharp swings in exports risk can suspend contracts, shake market confidence and potentially shift foreign investors toward competing countries, Gamze Saner noted. However, some foreign investors see it as a moment to bank on scarcity.

Unable to insure

To shield farmers from weather-driven losses, Turkey launched TARSIM in 2006 – a state-sponsored insurance scheme with the government covering about half to two‑thirds of the premium. To qualify, farmers must register their land in the Farmer Registration System (ÇKS).

Yet, small family farms often work informally, Gürer explained. They share land and lack title deeds. This leaves them unable to register or secure insurance. Of 5.5 million farmers affiliated with the Union of Chambers of Agriculture, only 2.3 million appear in the ÇKS. About half of them are insured.

Moreover not all insured farmers are covered for frost damage, grape grower Ayhanlı explained, citing the high cost and rarity of such events.

“We got insurance for hail. But we hadn’t done it for cold,” Ayhanlı told Turkey recap.

He added that getting compensation for frost damage can be difficult, noting that if the cold hits just as the vine begins to bud, insurers may claim there’s no damage and refuse to cover it.

Another reason many farmers remain unregistered, Bülent said, is the limited state support offered to registered farmers. Yet that decision may now prove costly.

Turkish Pres. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has repeatedly vowed to compensate all registered farmers, including those without insurance. Justice and Development Party (AKP) deputy Nilgün Ök reiterated during a July 17 meeting of the special frost commission that only registered farmers would receive compensation.

These moves will exclude many unregistered farmers, Gürer emphasized during a recent commission meeting, adding that the lack of damage assessments for those without ÇKS registration has left the frost’s true impact unclear.

“Given the scale of this disaster, damages for all producers, whether registered in the Farmer Registration System or not, should be covered,” Gürer told Turkey recap. He also called for debts to be deferred, interests erased and additional credit lines.

Currently, farmers’ total bank debt stands at a whopping 1.03 trillion lira. Meanwhile, farmers note that frost damage has skyrocketed maintenance costs, raising fears of further crippling debt.

“Producers have no money in their pockets to cover expenses,” Gürer said, adding that future harvests could be at risk as farmers are unable to afford essential supplies.

The special commission’s head, AKP lawmaker Adem Korkmaz, has acknowledged TARSIM’s gaps in coverage and roll-out, stating that Turkey’s insurance model must adapt to rising climate risks. According to Korkmaz, the solution is a basic compulsory insurance and an optional one with better coverage.

As of mid-July, TARSIM has paid out about 17 percent of the estimated damages, according to the agriculture minister. While relief for registered farmers may take until November, Erdoğan said at an agriculture meeting on June 28, where he also laid out a new loan package to finance greenhouses.

Turkey recap requested comment from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, but did not receive a reply at the time of publication.

Climate change coming for all

With no country in the Mediterranean harder hit by climate change than Turkey, Levent Kurnaz, head of Boğaziçi University’s Center for Climate Change Studies, urges farmers to look beyond mitigation measures that guard crops from cold.

“Agricultural frost is a matter of chance,” Kurnaz told Turkey recap.

Though connected to climate change, it won’t necessarily bring more frequent shock frosts. Moreover, warming poles will eventually leave no cold air to spark them, he explained. Instead, Kurnaz warns, drought and water scarcity loom as far more potent threats.

“We have to stay away from crops that need a lot of water,” Kurnaz said, adding Turkey should also avoid non-native produce, like avocados.

A recent UN report noted that 80 percent of Turkey’s agricultural land faces drought in the next five years as global temperatures climb. The first nine months of 2025 mark the country’s driest period in over 50 years. This has further battered yields, including strategic foods, such as cereals.

“After dealing with frost, now the issue is drought,” Bülent said. “It’s very clear, this agricultural system is not sustainable.”

In Denizli, the vineyard owner Ayhanlı stays defiant. He now hedges his risks by diversifying crops and splitting land into smaller plots. He planted artichokes, started raising sheep and is investigating which grape varieties are most resistant to frost. This, he hopes, will help prevent disaster from striking everywhere at once.

“I have been doing this for 40 years,” Ayhanlı said. “We’re not giving up.”

Turkey recap is an independent, reader-supported newsletter that helps people make sense of the fast-paced Turkey news cycle. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Subscribe here on Substack (or on Patreon for discount options). Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools.

Turkey recap is produced by our staff’s non-profit association, KMD. We are an affiliate of the Global Forum for Media Development and aim to create balanced news that strengthens local media by supporting journalists in Turkey.

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief

Emily Rice Johnson, Deputy editor

Günsu Durak, Turkey recap Türkçe editor

Ceren Bayar, Parliament correspondent