ISTANBUL—In the mid-2010s, when Turkey’s economy was still running strong, Deniz Akkar was a newly appointed public school teacher working in central Istanbul.

She eagerly awaited the day she would be eligible for a green passport—a perk for Turkish public servants that allows visa-free travel to Europe, bypassing often lengthy and costly visa procedures.

By the time she finally got the document a decade later, however, her hopes for occasional getaways had been nixed by Turkey’s cost of living crisis.

Despite climbing the career ladder to a senior position at the Istanbul municipality and taking on a second job as a book editor, Akkar’s salaries failed to keep up with the country’s high inflation figures.

This not only left the pages of her passport blank but has also started limiting her ability to go out at all.

“Life feels like walking on a tightrope nowadays,” the 44-year-old Akkar told Turkey recap, requesting the use of a pseudonym due to her position as a public servant.

She added that these financial constraints have gradually carved away much of her social life and have increasingly left her fearing that she would not be able to afford treatment if she were to fall seriously ill.

“If I were to catch a disease, I don’t have the budget or savings aside to get the required care,” Akkar said.

Akkar is among the many urban middle-income earners who hold university degrees and stable jobs in Turkey, but whose purchasing power has been eroded to precarious levels due to soaring living expenses and salaries that have failed to keep pace.

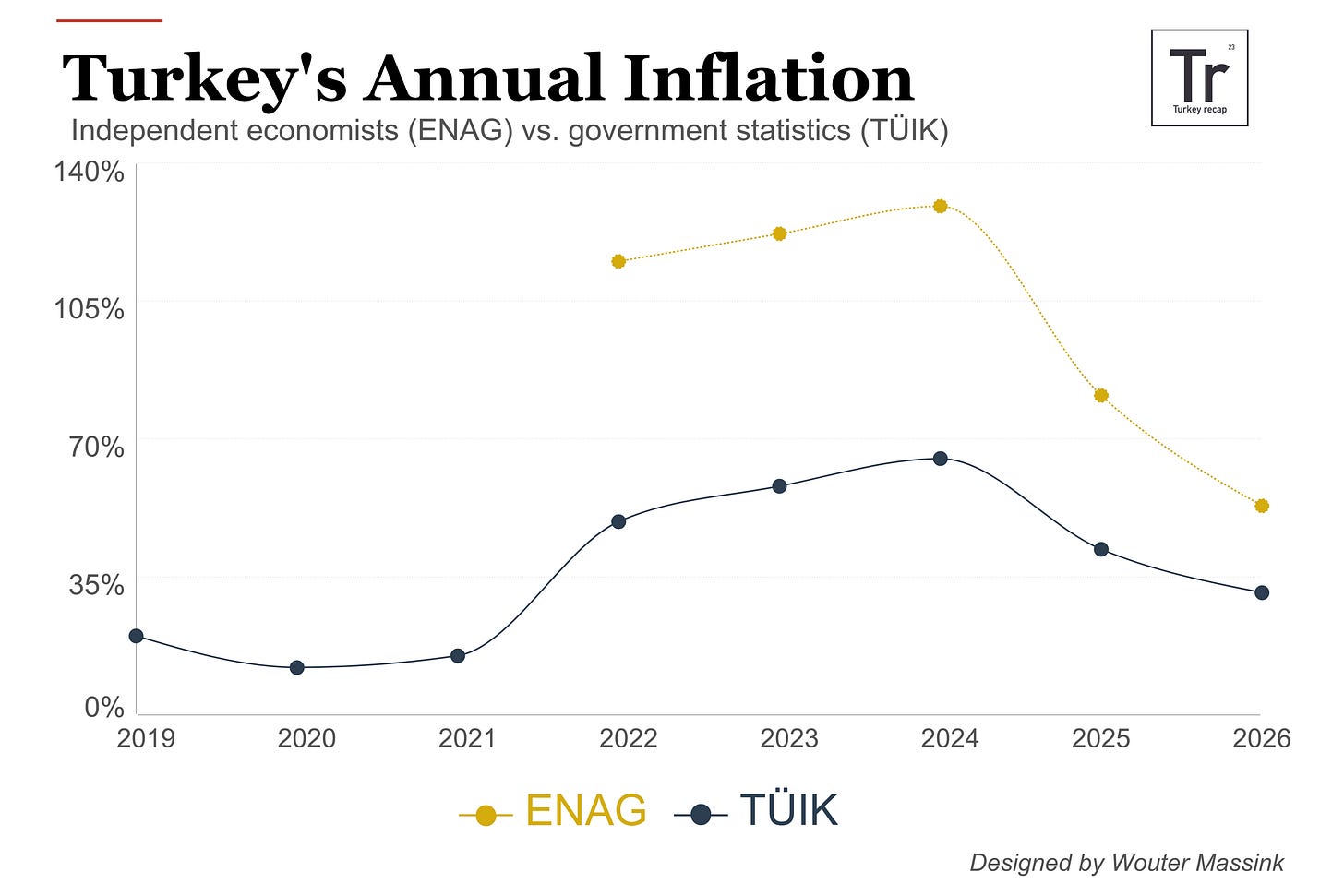

The trend shows little sign of slowing, despite the recent cooling of Turkey’s official inflation rate from the hyper-inflationary peaks of previous years.

Melting minimum wages

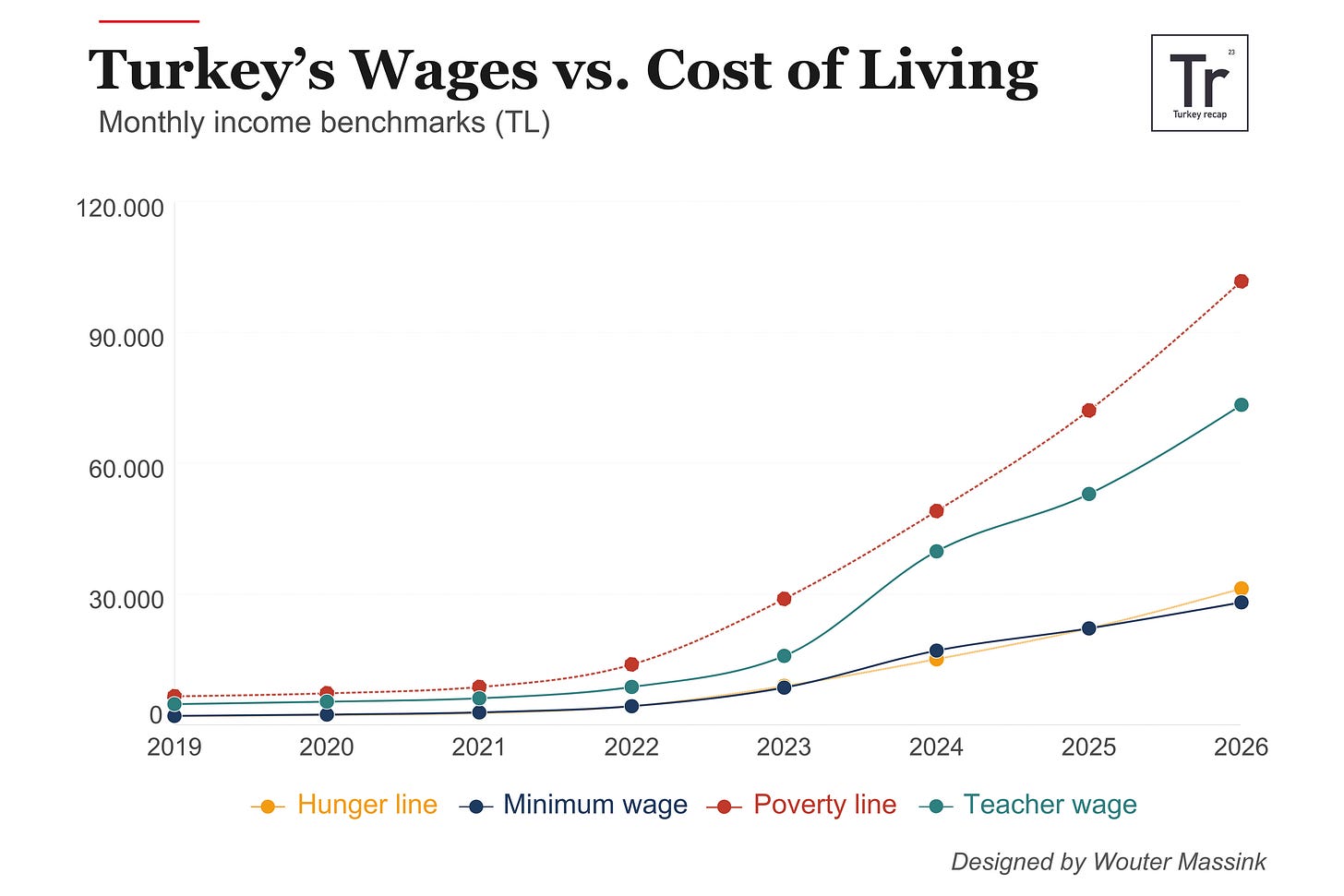

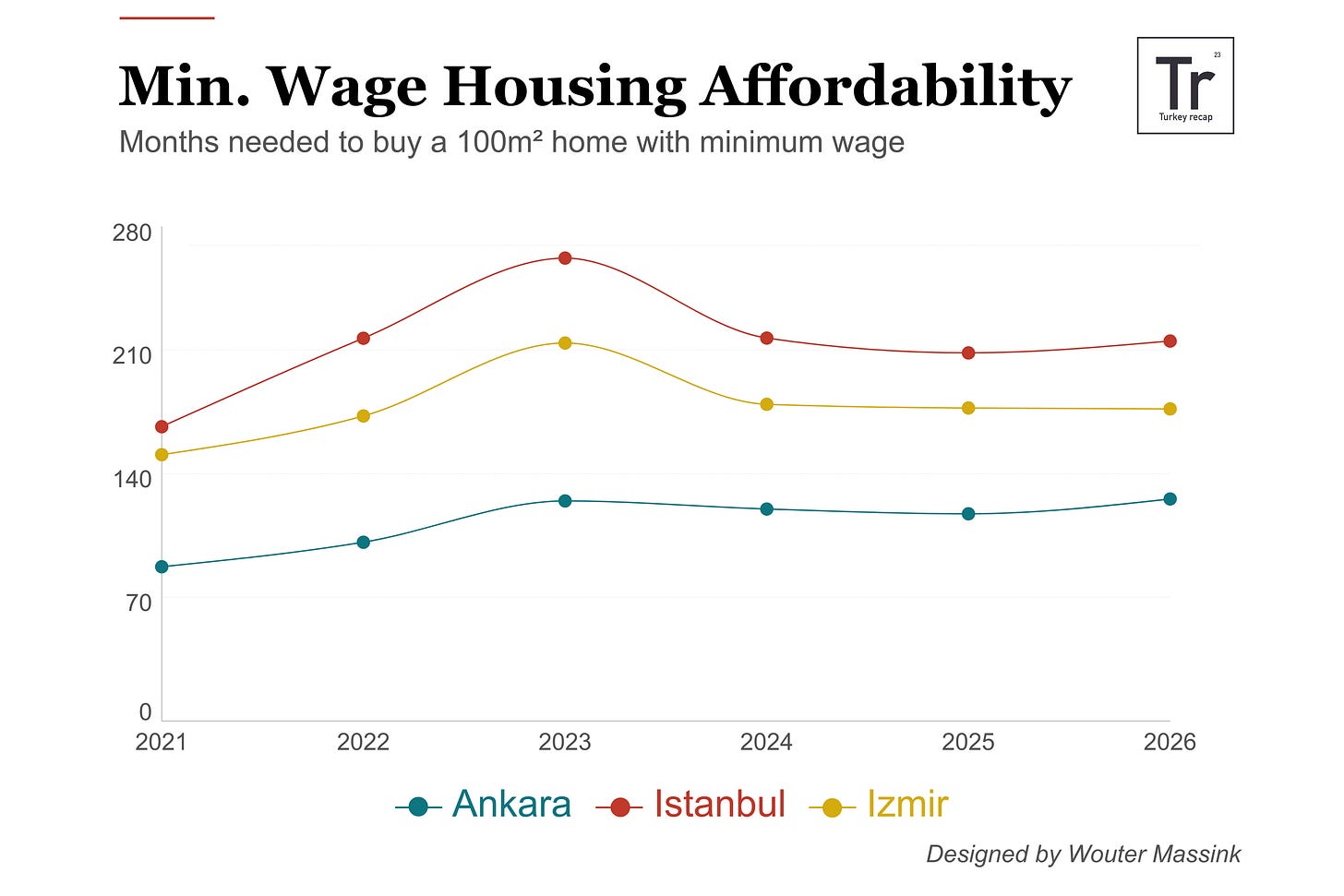

In January 2026, the long-awaited annual minimum wage hike was announced at 27 percent, bringing the monthly wage to 28,075 lira.

This marked the first time the minimum income came in below the hunger line, set at around 30,000 lira—the lowest salary required to meet basic nutritional needs for a family of four, according to calculations by the Turkish trade union TÜRK-IŞ.

“This figure is unacceptable to minimum wage earners, the public, and ourselves,” TÜRK-IŞ Pres. Ergün Atalay said following the announcement. “This amount doesn’t cover food, rent, education or transportation.”

Most basic expenses rose by significantly higher rates, from around 30 to nearly 50 percent over the same period, according to recently published official figures. Some experts suspect these numbers to be even higher.

Beyond the roughly 9 million people earning the minimum wage, it also serves as a benchmark for other salaries, with many sectors indexing wages to it or raising pay by even less.

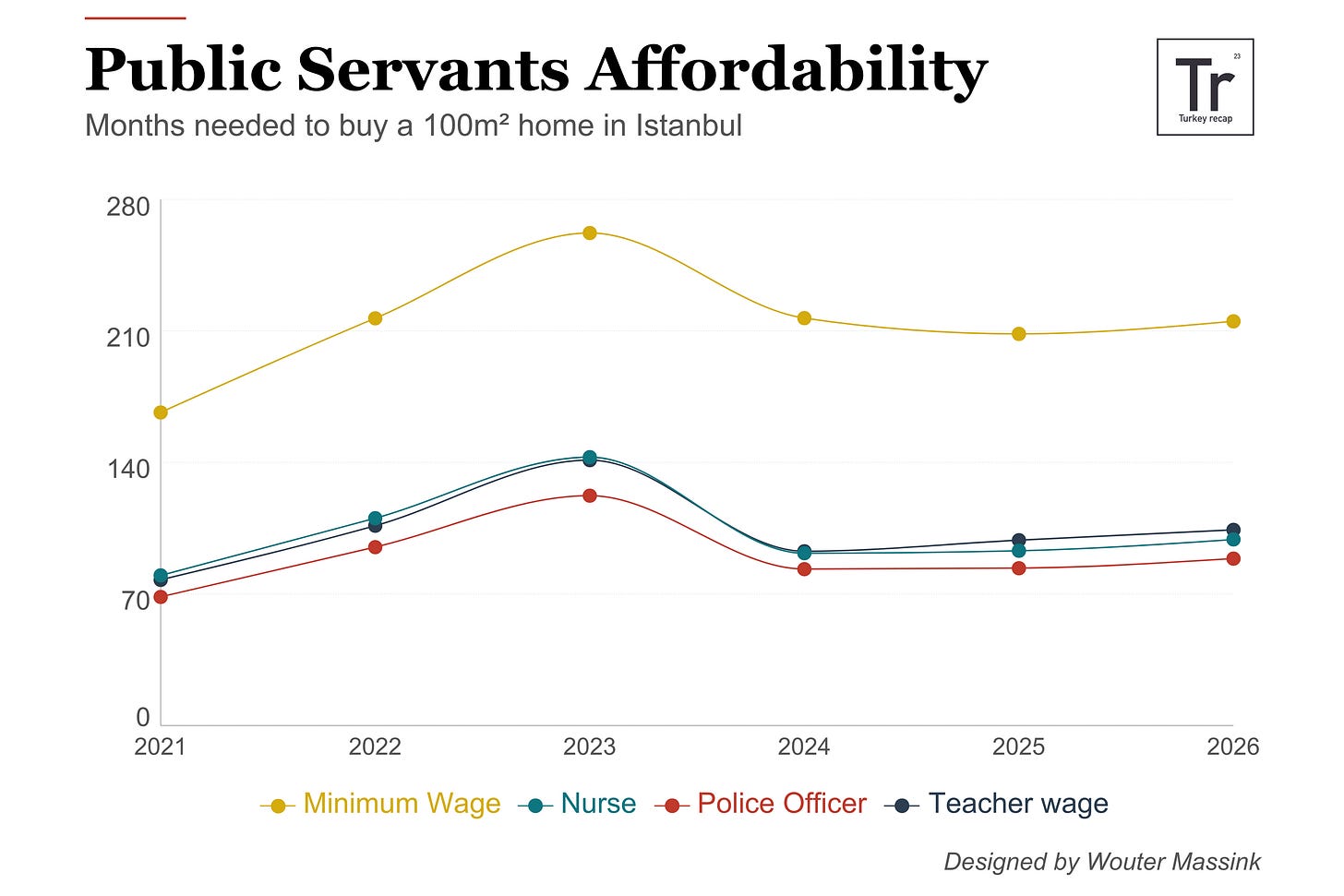

Civil servants, although receiving adjustments twice a year, saw their most recent raises of around 18.6 percent in January 2026.

As a result, the salaries of many teachers, nurses, and police officers are now roughly 20,000 lira below the poverty line, the minimum household income required to live with human dignity, which TÜRK-IŞ places at just above 100,000 lira.

“Despite inflation seemingly going down, prices are still very high, and wages are not keeping up. So, the crisis deepens,” Can Selçuki, an economist and director of Research Istanbul, told Turkey recap.

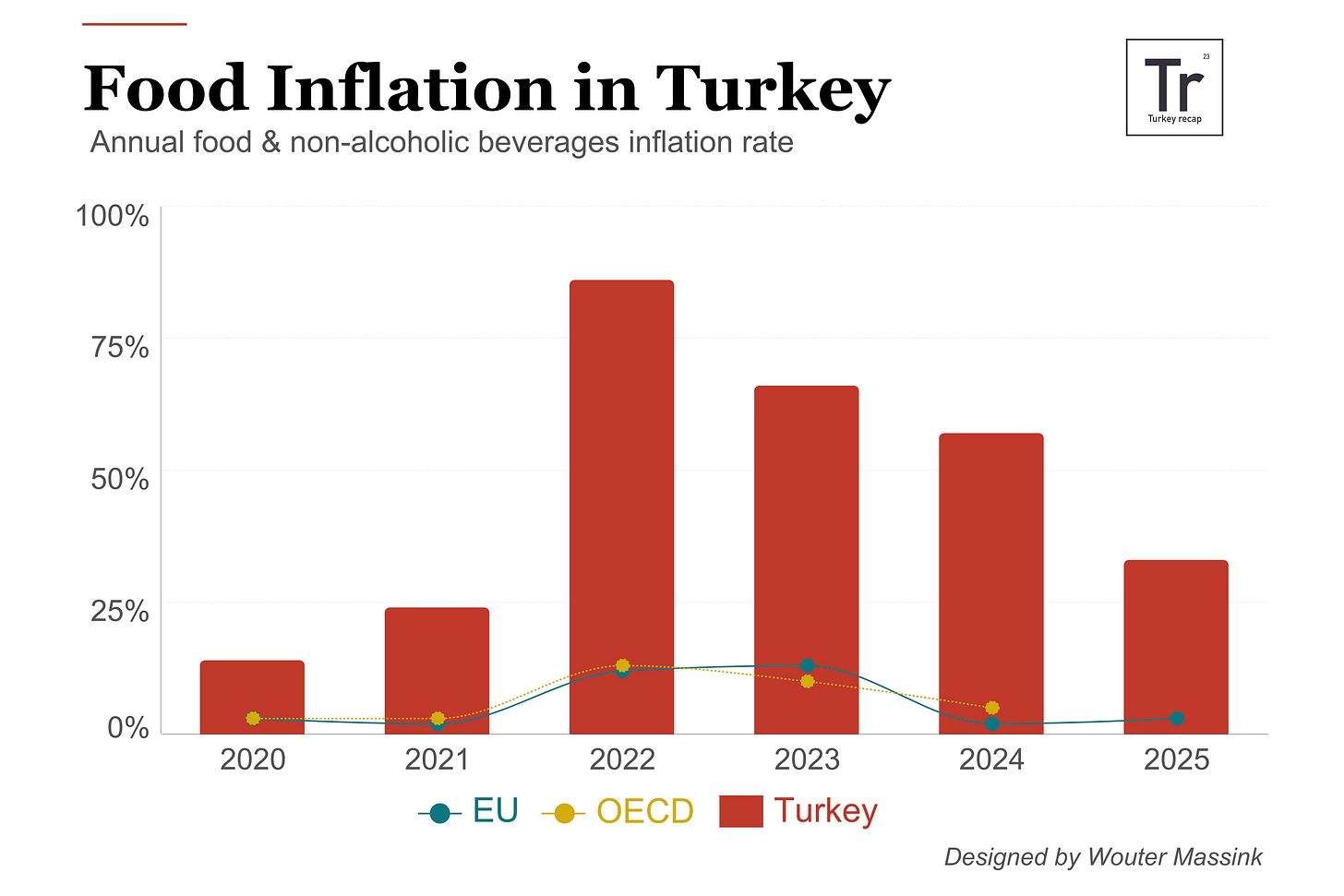

He added that as inflation persists throughout the year, the gap between income and costs will only widen, leaving Turkish households with an increasingly smaller share of their budgets allocated to food.

“For almost three to four years now, Turkish households have been continuously losing purchasing power,” Selçuki said. “Rather than decreasing the number of times they eat out, people are now decreasing the amount that they actually eat.”

Stabilization at a cost

One of the main reasons for lagging wage increases has been a shift in economic policy following the 2023 election victories by incumbent Pres. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP).

After years of unorthodox policies centered on low interest rates that fueled runaway inflation, the current reforms under Finance Min. Mehmet Şimşek applied tight monetary policy and fiscal discipline.

These measures are apparently paying off as inflation fell last month to its lowest level since 2021, with rent inflation also dropping to its lowest level in 34 months. The Turkish Central Bank’s total reserves have also doubled since the implementation of Şimşek’s program.

However, with the next elections scheduled for 2028, resolving the cost of living crisis could mean a return to expansionary policies and increased public spending.

“[This is,] from an electoral perspective, obviously the way to solve this,” Selçuki said.

Recent opinion polls indicate many voters, including those aligned with the AKP, view the country’s economic management negatively, with large majorities across the political spectrum stating they had hoped for higher minimum wage increases.

Handing out cash during election times, however, would not be sustainable in the long term, according to Selçuki.

“Turkey needs to do structural reforms, which include fixing its food supply chains, fixing its agriculture, and fixing its tax code in order to ensure efficient allocation of its resources,” Selçuki said. “Basically, Turkey needs more planning.”

Living on plastic

The current burden of declining purchasing power has fallen even more heavily on Turkey’s younger generations. A growing group of young people appears to have become disengaged from any economic participation, as an estimated one in four are neither in education, employment nor training.

Those who study have seen the value of their scholarships erode in recent years, forcing many to pick up additional work to get by. Graduates entering the workforce say their purchasing power has improved little, if at all, compared with their student years.

“I used to get by very comfortably with my scholarships. I could eat out three meals a day,” Meryem Akkoç told Turkey recap, a 29-year-old who recently started her career as a lawyer in Istanbul and prefers to use a pseudonym. “But now, I am a professional. I graduated from a good university and yet, while working, I experience much more [financial] trouble.”

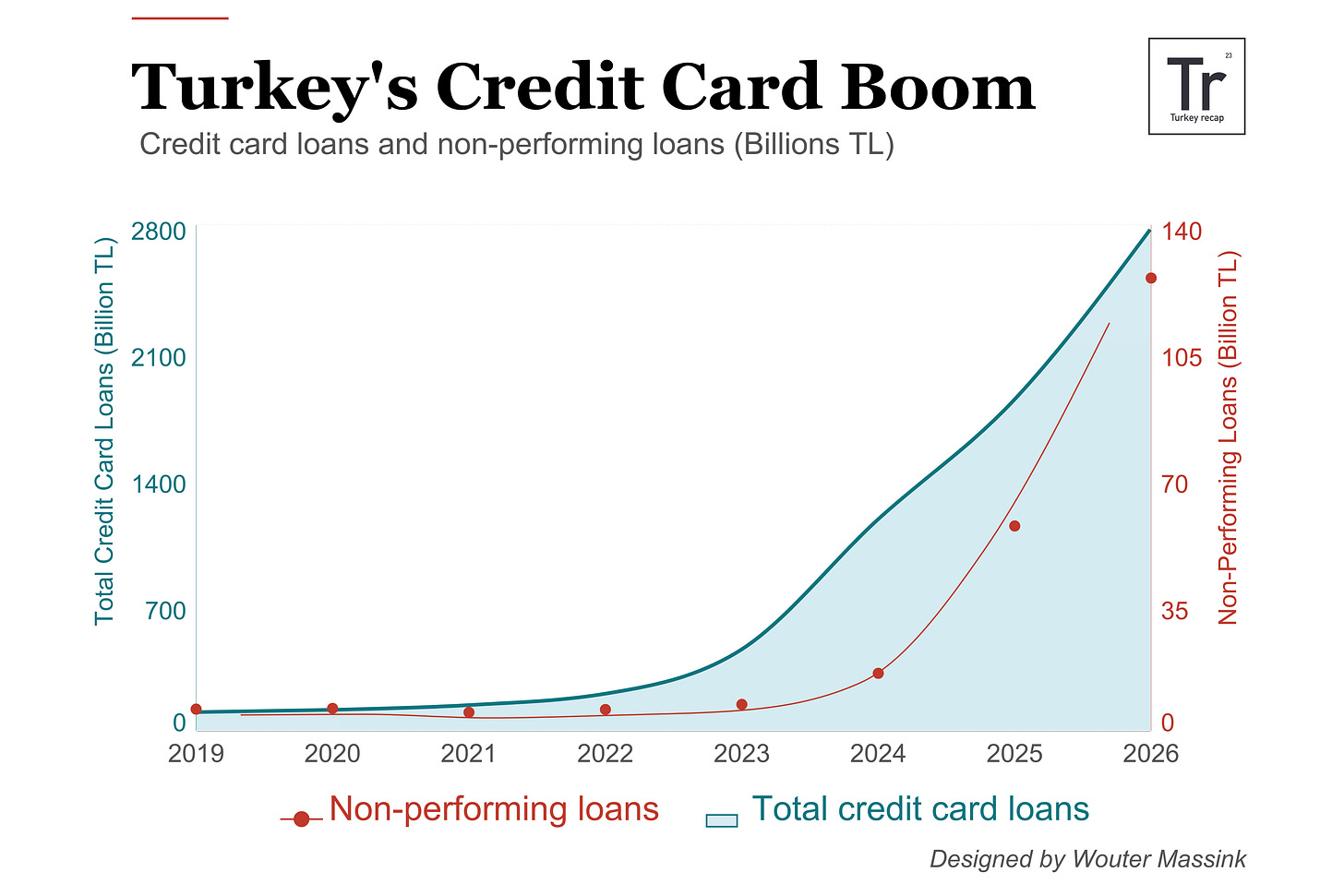

Amid such budget woes, many have resorted to credit cards to cover basic expenses. Turkey has become one of Europe’s top markets for credit card use, holding an estimated 142 million cards, or about 1.6 per person.

According to data from the Banks Association of Turkey, every day approximately 12,000 people in Turkey take out loans for the first time, and an average of 4,000 people fall into debt.

“We embrace credit cards to meet needs. Everyone’s debt grows like an avalanche,” Akkoç said.

However, especially over the past two years, a growing number of people are struggling to repay those debts. In 2025 alone, credit card debt more than doubled, and legal cases over unpaid personal debts have risen to over 2 million, nearly twice the number recorded in 2023.

These figures have become a thorn in the side of Turkey’s Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency, which recently introduced new regulations to tighten credit card limits and ease repayment pressures.

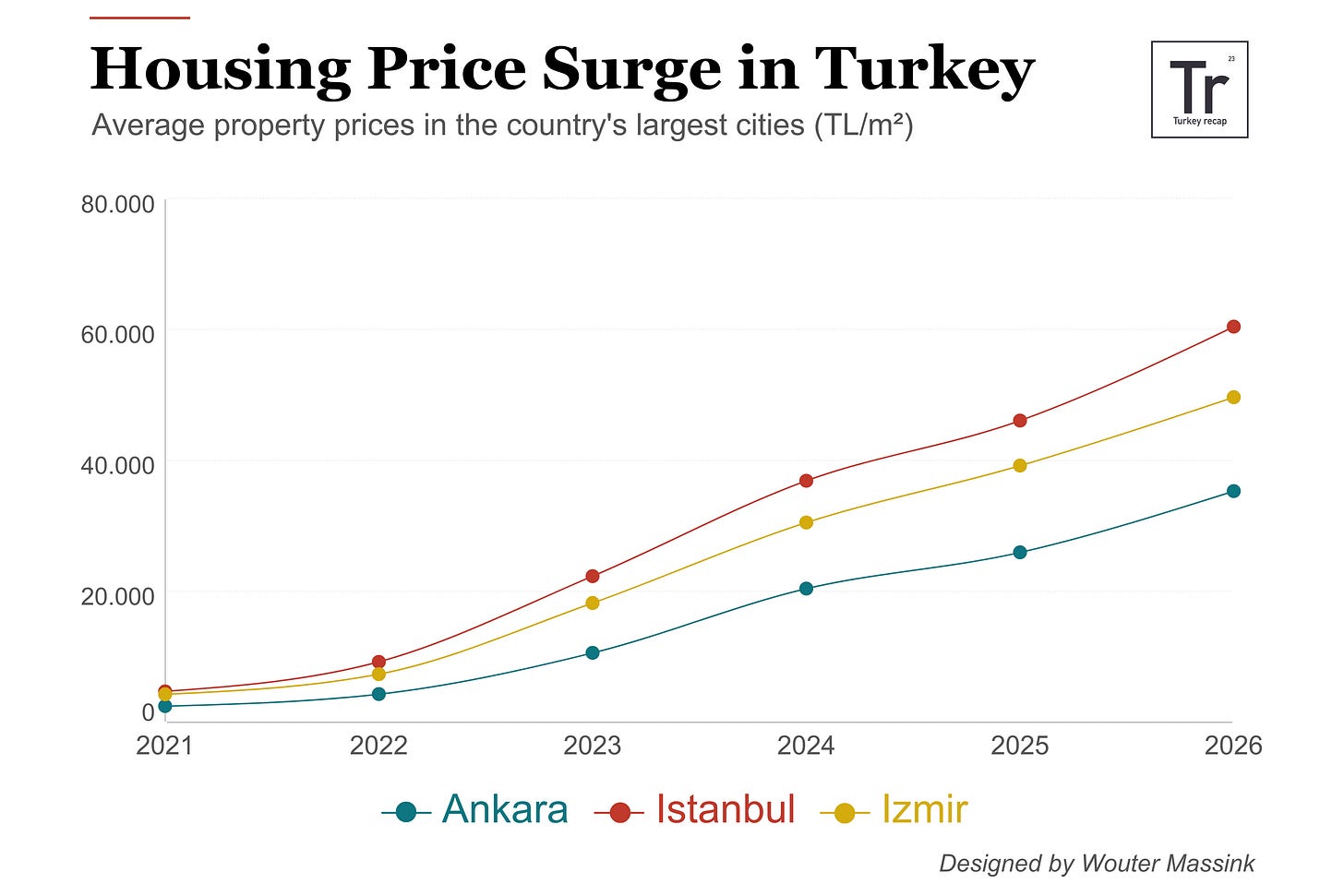

For Akkoç, who still lives with her mother, her financial struggles also mean that getting her own apartment is out of reach.

“Renting a place equals a salary,” Akkoç said, underlining how rents have reached parity with average monthly salaries.

She contrasts her situation with that of her father, who was able to buy property while holding a blue-collar job.

“Nowadays, it is impossible for someone to buy something by working and putting money aside,” she said.

Methodology and data sourcing

Credit card figures were drawn from weekly sector data published by Turkey’s banking regulator.

Inflation estimates rely on the official consumer price index provided by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜIK) and independent alternative inflation calculations compiled by researchers at ENAG, following growing skepticism about Turkey’s official tally.

Food inflation comparisons are based on data provided by the OECD.

Cost-of-living estimates are derived from TÜRK-IŞ calculations of hunger and poverty thresholds for a four-person household, which include basic food costs as well as expenses such as housing, utilities, transport, education and health.

Average housing prices have been compiled by using data provided by real estate site Endeksa.

Wage comparisons are based on publicly reported salary ranges for selected public-sector professions from multiple sources: 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, 2026.

Note: Wage statistics do not include biannual hikes. Instead, they focus on year-by-year increases. During Turkey’s hyperinflation years, biannual hikes were more common. However, the trends has shifted back to annual hikes in recent years.

Turkey recap is an independent, reader-supported newsletter that helps people make sense of the fast-paced Turkey news cycle. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Subscribe here on Substack (or on Patreon for discount options). Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools.

We are an affiliate of the Global Forum for Media Development and aim to produce balanced news that strengthens local media by supporting journalists in Turkey.

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief

Emily Rice Johnson, Deputy editor

Ceren Bayar, Parliament correspondent

Yıldız Yazıcıoğlu, Parliament correspondent

Günsu Durak, Stüdyo recap editor

Demet Şöhret, Social media and content manager