To find the press conference by media groups in Diyarbakır last Wednesday, one only had to follow the lines of riot police. Arriving at the scene, plain-clothed police asked for press cards and took notes on who was attending.

“The other people we know, but we don’t recognize you,” the officer responded when asked why he needed to see a press card for an event in a public space.

The next day, at the same place during a separate press statement, a police bus was parked outside of the nondescript building, which hosts a Dicle Fırat Journalists’ Association office. Again, there was a group of plain-clothed police, this time easily mistaken for a group of bored guys hanging out. They were monitoring who entered the building, which also hosts an İYİ party office.

“They take pictures of us every time, even though they know us,” said Mesopotamia Agency (MA) Diyarbakır correspondent Eylem Akdağ.

While these are just two small examples, they provide a window into the day-to-day pressure on local journalists. Last week, 12 Kurdish journalists were detained, nine of which were later arrested on terror-linked charges.

During that process, Turkey recap visited Diyarbakır and interviewed staff members at the impacted news outlets, MA and JINNEWS, as well as Artı TV and the Dicle Fırat Journalists’ Association to ask how they assess press freedom in Turkey what they expect from the recently passed disinformation law.

Rights advocates have said the new measure will further restrict free speech and the work of non-government aligned media organizations, but for many Kurdish journalists in Diyarbakır, the law is more of the same, though now with a stronger legal basis.

Disinformation law

Dicle Müftüoğlu, co-chair of the Dicle Fırat Journalist Association and MA contributor, said the disinformation law threatens whatever is left of press freedom, however, she doubts it will radically change anything.

“It only makes it more official,” she said. “Actually, this government did a lot of similar things up until now. People already went to jail for sending a tweet, unfortunately they got detained, arrested, had court cases, and got sentenced. I also was sentenced to 1 year and 3 months in jail because I shared news from my agency on Twitter.”

Speaking after reading a statement in Kurdish, JINNEWS editor Roza Metîna, told Turkey recap: ”They say disinformation law, but we call it the censorship law or the law for the organized violation of journalists’ rights.”

Metîna preferred to answer the questions in Kurdish, as well, but since Turkish was the only common language between the reporter and interviewee, and the answers would be translated to English, she agreed to speak in Turkish.

She noted there’s been pressure on the media for years, “but with this law, they want to guarantee this pressure by law. They want to make what they are already doing legal and say ‘Look, we are behaving according to the law.’”

MA editor Sedat Yılmaz shared a similar view: “Between 8 and 16 June, when the law was not yet passed, they took 16 of our friends,” he said, referring to 16 Kurdish journalists jailed since in June this year.

“For the Kurdish press, there will not be any change,” Yılmaz added.

Journalist detentions

Sitting in the Mesopotamia Agency office, Yılmaz is temporarily taking over the role of chief news editor, filling in for an arrested colleague. He insisted the recent detentions have not affected the agency’s output. Instead, they have motivated him further.

“If you normally would work five hours, now you are working ten hours,” Yılmaz said.

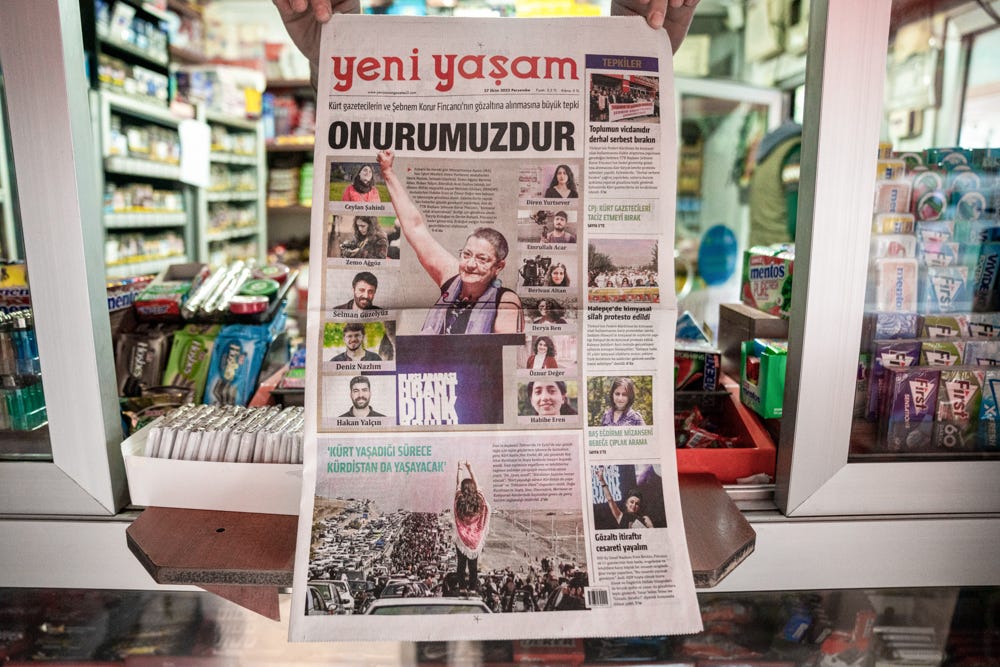

Those detained on Oct. 25 in early morning raids across the country were: MA news editor Diren Yurtsever, MA reporters Emrullah Acar, Zemo Ağgöz, Berivan Altan, Selman Güzelyüz, Deniz Nazlım, Ceylan Şahinli, Hakan Yalçın and former MA intern Mehmet Günhan. From the all-female JINNEWS, Öznur Değer and Habibe Erenare were detained. In an unrelated case, a 12th journalist, JINNEWS reporter Derya Ren, was detained the same day in Diyarbakır.

In addition, police searched the MA Ankara bureau for six hours, with authorities taking computers, hard disks, notebooks, a microphone and a newspaper archive of the now-shuttered pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem.

According to a statement the Ankara Provincial Security Directorate posted on Twitter, 11 journalists were suspected of “inciting hatred and hostility upon the public.” The operation was part of an anti-terror operation against MA, an agency the statement claims operates under the orders of the “PKK/KCK terrorist organization press committee.” In a follow-up tweet, footage of the detentions was accompanied by sensational music.

According to the Media and Law Studies Association, the journalists were questioned about their membership to the Dicle Fırat Journalists’ Association and whether they took orders on behalf of that organization. Following interrogations, at about 3 am Friday night, a judge cited “strong suspicion” the journalists “committed the offense of being a member of an armed terrorist organization” and ruled to arrest nine of them.

MA reporter Zemo Ağgöz (mother of a 1.5-months old baby) was released Thursday under house arrest and the former MA intern, Mehmet Günhan, was released Friday under judicial control measures.

Gürkan Özturan, a coordinator for Media Freedom Rapid Response, said the charge of taking part in or membership to an armed terrorist organization (read: the PKK), is often used by prosecutors in cases involving Turkish journalists, and Kurdish journalists, more specifically.

“Almost all journalists that are subjected to judicial harassment are accused of terrorism charges, but for Kurdish journalists there is an increasing targeting recently,” Özturan told Turkey recap.

Vaguely-worded anti-terror laws that allow for interpretation as authorities see fit are harming the democratic processes in the country, said Özturan, a former journalist who works for the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. He expects an increase in the number of raids and imprisonments against Kurdish journalists in the lead up to the 2023 elections.

“When we look at the accusations against Kurdish journalists, one cannot help but wonder if this is part of a political campaign to mobilize nationalist voters based on a conventional rhetoric that we have seen since the 1980s in Turkey,” Özturan said.

HDP MP Tayip Temel also underlined the frequent use of terrorism charges against journalists. During a visit to the Dicle Fırat Journalists’ Association, he told Turkey recap the government “calls everyone a terrorist, they are putting these terrorist claims to everyone and they definitely want to suppress the opposition media.”

For him, there was no doubt the journalists were just doing their jobs. “We know all the journalists that are detained. They are journalists,” Temel said.

When asked about the terrorism charges lodged against his colleagues, MA editor Sedat Yılmaz highlighted reports by international journalist organizations like Reporters Without Borders, and asked if the reports were accusing them or the government.

“For example, who incites hatred, racial discrimination, animosity against women and refugees, who is doing that?” Yılmaz asked. “Are we doing that or Yeni Şafak? Are we doing that or is Sabah doing that?”

International journalism organizations IPI, CPJ and IFJ condemned the arrests and called on Turkey to release the latest detainees and all other jailed journalists. In a statement, the Committee to Protect Journalists added the Turkish authorities must “stop harassing the Kurdish media in Turkey with baseless charges that typically end up being related to their journalism.”

“Continuous pressure”

Müftüoğlu, co-chair of the Dicle Fırat Journalist Association, remained adamant the disinformation law combined with the latest arrests would not silence journalists in Turkey. As evidence, she highlighted the bombings of media buildings in the 90s, the killing of around 30 journalists in the streets and the closure of many Kurdish media outlets following the 2016 coup attempt.

“Against all of this, we still stand tall,” Müftüoğlu said.

Mehmet Çakmakçı (“my official name, but everyone calls me Şiyar Dicle”), a correspondent for Artı TV who has worked in the region for 20 years, said southeast Turkey has always been a difficult place to work.

“In some aspects, it has become better. In other aspects it got worse, but it never stopped,” Çakmakçı said. “There has been continuous pressure.”

Despite that pressure and other difficulties – “You’re not earning any money either,” Çakmakçı noted – most of the Kurdish journalists interviewed by Turkey recap said they remain passionate about their jobs and are determined to stay on task.

Still, the threat of house raids is constantly in the back of their minds. One journalist said, when taking a shower, they often think: “What if they come to my door right now?”

Or as MA reporter Eylem Akdağ described (and other interviewees echoed): “Every night when you put your head to your pillow, you think, will they come for me tomorrow morning?”

This report was produced by Turkey recap with support from the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Turkey and the IPS İletişim Vakfı.

Turkey recap is an independent platform supported by readers via Patreon, where members get access to our back channel, news tracking tools, calendar and more.

If you liked this report, subscribe here or forward it to a friend. Send us feedback, pitches and requests. We’re working to grow this platform: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Diego Cupolo, co-founder + editor @diegocupolo

Verda Uyar, freelance journalist @verdauyar

Ingrid Woudwijk, freelance journalist @deingrid

Gonca Tokyol, freelance journalist @goncatokyol

Batuhan Üsküp, editorial intern @batuskup